Women in Buddhism: Seeking Enlightenment and Equality

Buddhism promises enlightenment to all, yet women have navigated unique obstacles in this spiritual journey.

Buddhism promises enlightenment to all, yet women have navigated unique obstacles in this spiritual journey.

Table of Contents

ToggleBuddhism is quite explicit in the fact that spiritual development, and ultimately enlightenment, is a goal for all sentient life, male and female. Yet, women have faced more obstacles on the spiritual path since the inception of Buddhism two and a half thousand years ago, and for a variety of different reasons.

In the following article, we shall explore the experiences of women in Buddhism from four different perspectives: the history of female involvement in the early developments and spread of Buddhism, the philosophical teachings of Buddhism as regards spiritual development, the development of Buddhist cultures around the world in more modern times, and the feminist perspective on gender equality in contemporary Buddhist practice.

The cultural milieu of ancient India was one of patriarchy and hierarchy, underpinned by the caste system. The early Vedic religion, which was dominant in India before the emergence of Buddhism, reinforced gender inequality in spiritual pursuits, as women were expected to focus on maintaining the household and childcare.

There were also a number of religious practices that actively discriminated against women in ancient India, such as Sati, where widows were encouraged to immolate themselves atop their deceased husband’s funeral pyres.

Amidst these archaic cultural expectations, around the 6th century BCE, Siddhartha Gautama – the historical Buddha – would challenge the fundamental basis of discrimination for a spiritually oriented society, teaching that women and men possess the same potential to become liberated from suffering. The route to liberation was one of personal effort and spiritual practice, which is independent of social caste, and so women were welcomed into the monastic order.

The first disciples of the Buddha were monks, and the very first Buddhist nun, Mahapajapati Gotami, was the Buddha’s own aunt and stepmother.

Ananda, who was one of the Buddha’s key disciples, was instrumental in the establishment of the order of nuns – the “bhikkhuni” order – for it was he who reasoned the Buddha to accept Pajapati as the first female disciple.

However, while the enabling of the spiritual goals of women was a great step forward for gender equality in Indian religion, women were nevertheless required to agree to more rules than men. Moreover, while the Buddha was aware of the equal possibility of liberation for women, there were men who remained heavily influenced by the previous cultural and religious expectations.

It is clear that there were male allies of women in the Sangha, like Ananda, whose efforts to address gender discrimination laid the groundwork for further progress in the years that followed.

Following the establishment of the bhikkhuni order, a number of women became highly influential in early Buddhist practice. The Anguttara Nikaya, part of the Pali Canon of Buddhist scriptures, mentions many female exemplars of spiritual achievement.

Pajapati was the foremost disciple in seniority, Khema was the foremost in great wisdom, and Uppalavanna was the foremost in psychic powers. Additionally, Yasodhara, Siddhartha’s wife before he became an ascetic sramana, also became a bhikkhuni, and also achieved nirvana – the cessation of suffering – in her lifetime.

Of course, the establishment of the bhikkhuni order did not eliminate all discrimination within the Sangha. Historical records reveal that throughout the early developments of Buddhism, there were monks who continued to view women as inferior, and there were women who were subjected to harassment and abuse.

In the 3rd century BCE, the Indian Mauryan Empire fell, and new dynasties emerged with distinct cultural traditions and practices. Buddhism was also spreading outside of India, and by the 1st century CE, disputes regarding the Buddha’s teachings on gender equality were becoming more common, and the bhikkhuni order began its slow demise.

Throughout the centuries that followed, India fell victim to repeated invasions from various groups, including the Kushans, the Huns, and the Turks. Faced with the economic, political, and societal upheavals that resulted, less women chose, and had the means to choose, to seek ordination as nuns. Efforts to maintain the bhikkhuni order diminished, and by the 10th century CE, it had largely vanished from the majority of Buddhist traditions.

The foundational teachings of Buddhism are surmised by the Four Noble Truths, which state that:

The Noble Eightfold Path then consists of the practices one must follow on the path to liberation, and the ability to pursue these practices is completely independent of gender.

There are, however, other philosophical and theological elements of Buddhism that reveal more direct insights into the relationship between gender and spirituality.

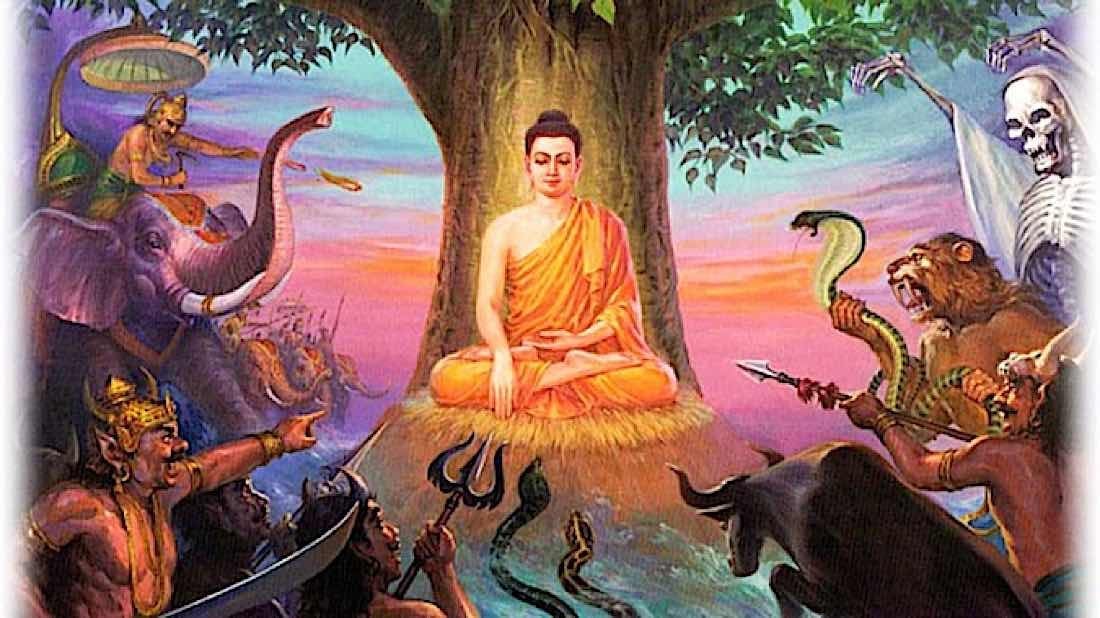

In the famous story of the Buddha’s enlightenment under the bodhi tree, the demon Mara, which is a personification of all those desirous forces that prevent us from realizing enlightenment, appeared to the Buddha to question his worthiness. The Buddha gestured to the ground, invoking Mother Earth, who in the Vedic tradition was personified as the goddess Prithvi, to witness his awakening. The story indicates the importance of the female element of spirituality, given that he gestured to the earth and not the heavens.

The divine feminine, in Buddhism as it was in the earlier Vedic religion, represents certain qualities of reality, such as compassion and wisdom, that complement the masculine aspect that is often referred to as “Father Sky”.

Prajnaparamita means “the Perfection of Wisdom” or “Transcendental Knowledge” and is personified as the “Great Mother” archetype. It was also associated with a female bodhisattva called “Tara”.

Texts from the Mahayana and Vajrayana sects of Buddhism describe a number of other female bodhisattvas, which can be interpreted as archetypal constructs that express certain qualities of Buddhahood that are traditionally associated with femininity, like compassion, loving-kindness, nurturing, and intuition.

The principal bodhisattva of compassion is known as “Avalokitesvara”, who is portrayed as an androgynous character. Sometimes Avalokitesvara appears female, sometimes male, and sometimes both at once. This reveals the complementarity of male and female qualities in the divine, both of which must be embraced to move along the spiritual path.

Anatta is one of three central tenets on which the whole of Buddhism is built – the “three marks of existence”. It translates to something like “without self-existent essence” and refers to the doctrine that the human being is absent of an unchanging, permanent self or essence.

Nagarjuna, who has been referred to as the second most important thinker in the entire history of Buddhism, elaborated that the notion of “self” under attack is that of one’s personal identity, including one’s mental and physical personality.

Buddhism teaches that attachment to one’s identity is the cause of negative qualities like pride, selfishness, and ultimately suffering. That is because this identity is an illusion, devoid of self-existent essence, and it shields us from the ultimate truth of our being.

Accordingly, gender, which is an element of the mental and physical personality, is also an illusion, and therefore something from which all individuals on the path to enlightenment must learn to detach importance.

Despite the aforementioned teaching on the illusory nature of the material self, Buddhism is also renowned for its teachings on rebirth, and this has led to a lot of conflict and misunderstanding. The question is, if the idea of a permanent self or enduring soul is fallacious, what is left to be “reborn”?

The answer is that Buddhism does not teach that souls become reborn through many individual lives, but rather that an individual life creates conditions within consciousness (“karma”) that have effects persisting after that individual life ends (a bit like how a footprint left in the sand will influence the flow of water over it after the foot is removed). Thus, the previous life may have some influence into the nature of the subsequent life, without any transfer of individuality taking place.

Nevertheless, we find many instances in the Buddhist canon that indicate the idea that it is better to be “reborn” as a male, or that a woman that is close to achieving enlightenment in one life will be reborn as a man in the next.

Now, it’s possible that the karma of a spiritually advanced woman influences the reincarnation of a male with residual attributes of that woman, but I have struggled to find any explanation as to why this would be so. Tenzin Palmo, a British bhikkhuni in the Tibetan tradition, certainly doesn’t think there is any good reason for the idea, for she has made a vow to attain enlightenment in the female form, no matter how many lifetimes it takes.

If I might impart an opinion, the idea that it is better to be reborn as a man is a form of gender discrimination that still persists within the religion. I believe that the idea is a result of non-theological cultural influences, and that it conflicts with the Buddha’s own teachings on gender equality, and the ability for women to achieve enlightenment in thislifetime.

In addition to the implications of gender equality within Buddhist teaching, there were also women that played important roles in the development and transmission of Buddhist thought in the Middle Ages, after the fall of the bhikkhuni order.

In the 8th century, an Indian tantric master called Padmasambhava,along with his equally venerable female consort, Yeshe Tsogyal, began teaching Vajrayana Buddhism in Tibet. Together they were figures of incredible importance for the dissemination of Buddhism to Tibet, where both are now considered to be Buddhas in their own right.

Padmasambhava’s legend equals that of both Nagarjuna and Siddhartha Gautama, yet it is recognised that Yeshe Tsogyal’s spiritual development was equal to that of Padmasambhava’s by the end of her life. Indeed, Yeshe Tsogyal is recorded as having asked the latter about her allegedly inferior female form, to which she received the following reply:

The basis for realizing enlightenment is a human body. Male or female, there is no great difference. But if she develops the mind bent on enlightenment, the woman’s body is better.

Another important figure in the spread of Buddhism throughout Asia was Prajnatara, who is the 27th patriarch in a line of teacher-student relations that supposedly goes back to the Buddha himself. An official record of this individual’s gender is lost from the Buddhist canon, and Chinese Buddhism has generally assumed their gender as male, in keeping with all the other patriarchs. However, there is an oral tradition in India that understands her to be female, and in any case, the name “Prajnatara” is a synthesis of Prajna, meaning “wisdom”, and Tara, the female bodhisattva mentioned earlier.

Prajnatara was the teacher of Bodhidharma – the 28th patriarch – in the 4th century CE, and Bodhidharma is credited with transmitting the Buddhist doctrine to China, in the form of Chan. Chan would then become Thien in Vietnam, Seon in Korea, and Zen in Japan. So Prajnatara is indeed a very important figure in the history of Buddhism.

Any anthropological investigation into the roles performed by women in Buddhist communities around the world will naturally reveal a tremendous diversity in experience. Buddhism is now a global religion, and traditional practices and expectations of different cultures have shaped Buddhism to align with respective cultural standards.

Generally, there has been consistent progress in the revival of the bhikkhuni tradition in Eastern countries. In Sri Lanka, women have been able to become fully ordained in the Theravada tradition since 1996, and there has also been development in the same regard in India and Thailand.

However, in accordance with Vinaya tradition, which concerns the rules of the Buddhist Sangha, the ordination of bhikkhunis must be performed by an already established group of bhikkhunis, and these have been highly limited in number.

Nevertheless, in the Mahayana tradition, which abides by its own set of procedures, the Buddhist community has been more supportive of women in their participation and education within the religion. Alternative forms of ordination have been developed in countries practicing forms of Buddhism descended from Chinese Chan, including Taiwan (Chan), Vietnam (Thien), Korea (Seon), and Japan (Zen).

The developments in gender equality in contemporary Buddhist communities has been facilitated by the leadership of female practitioners in promoting the access to ordination. For example, in 1996, Bhikkhuni Kusuma, a Sri Lankan, was the first woman to gain full monastic ordination in the country in a thousand years, despite considerable controversy and opposition. Her ordination inspired the revival of the bhikkhuni order in Sri Lanka, where there are now over 3000 ordained nuns.

One of those nuns was Dhammananda Bhikkhuni, who was the first modern Thai woman to gain ordination as a bhikkhuni in 2003. Dharmmananda went on to establish the first and only monastery that exists today in Thailand at which women can become ordained.

Both of these women have greatly contributed towards an understanding of traditional Buddhist texts that embraces the theological gender equality that was present in antiquity. Between them, they have authored numerous books on contemporary issues in Asian Buddhism, and remain as inspirational figures for Buddhist women around the world.

Ordination for women has also steadily increased within the Western world, particularly in the Tibetan tradition of Vajrayana Buddhism. Freda Bedi was the first Western woman to receive full ordination in Tibetan Buddhism in 1966, and Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo is an American woman who was in fact recognised by the head of the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism, Penor Ripoche, as his successor and thus as a reincarnated lama, in 1987.

Women have also been instrumental in driving the popularity and accessibility of Buddhism for Western audiences. Helena Blavatsky founded the Theosophical Society in 1875, which syncretised teachings from Buddhism with Western esotericism, and was responsible for much of the early popularity of Buddhism in the West.

By her own account, Blavatsky made trips to Tibet where she was taught in Mahayana Buddhism. Regrettably, many of Blavatsky’s claims are dubious, and have no supporting evidence. Nevertheless, Blavatsky was the first Western woman – indeed, the first Western person – to officially convert to Buddhism through a traditional ceremony of precepts, which she received in Sri Lanka in 1880.

One reason to doubt Blavatsky’s account is the fact that Tibet was closed to Europeans during the 19th century. Yet, one woman who certainly did travel there to learn Buddhism, on several different occasions, was Alexandra David-Néel. Most famously, she managed to enter the city of Lhasa in 1924, and also met with the Dalai Lama, during his exile in India, in 1912. David-Néel authored over 30 books that greatly assisted in inculcating the rapid increase of Western interest in Eastern wisdom.

Buddhist feminism is a relatively recent movement that has been driven by American Buddhist activists and scholars such as Sandy Boucher and Rita Gross. The goal of the movement is, generally, to promote an understanding of the equality of men and women within the religion, but more specifically to increase the opportunity for women to enter positions of leadership.

The establishment of the Sakyadhita International Association of Buddhist Women in 1987 was also a significant step forward for women in Buddhism. The organization has brought together a global network of over 2000 women practitioners in 45 countries.

Similar organizations have taken root in Asia, such as the Buddhist Women’s Association in Japan, and, as we have already discussed, there are growing monastic orders offering full ordination for women in many countries throughout the continent. These communities will only continue to grow as the bhikkhuni lineage continues on its current momentum.

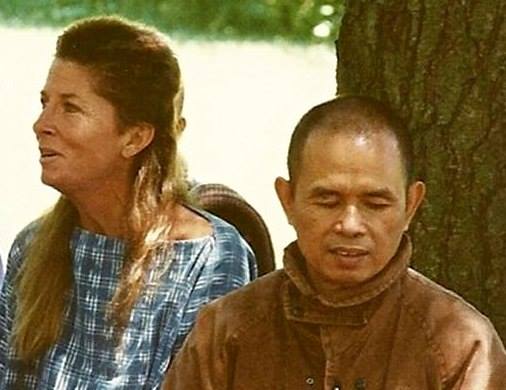

In recent years, there has been a growing effort to apply Buddhist ethics and philosophy to contemporary socioeconomic and environmental issues. Thich Nhat Hanh’s “Engaged Buddhism”, for instance, encourages the integration of mindfulness into everyday life as a means to stimulate social change.

A notable student of Thich Nhat Hanh, Joan Halifax, who is an abbess in American Zen Buddhism, has also been involved in extensive work on social issues, such as caring for the dying, as well as the relationship between science and Buddhism.

Engaged Buddhism is a framework that works to assist feminist scholars of Buddhism in promoting gender equality and justice. Through it, feminist critiques of gender hierarchy have brought attention to the ways in which certain Buddhistic traditions reinforce patriarchal attitudes and biases.

Traditional interpretations of certain Buddhist teachings have been challenged, as has the application of traditional interpretations to modern society. Overall, the drive towards recognizing more diverse and inclusive perspectives has helped to alter the course of modern Buddhism, as it becomes more engaged with modern society.

The women of Buddhism are not a monolithic group. There is a wide variety of experiences, and a wide variety of developmental stages in Buddhist communities around the world when it comes to the rights of women.

While there still is not full gender equality in the religion, we should be encouraged that efforts to address the social issues that remain in all religions, both within institutions and outside of them, are on the rise. We must recognize that many of these issues are cultural and social, not philosophical or theological, and all institutions are subject to the limits of the cultures they often outlive.

Women have played an instrumental role in the development of early Buddhism in antiquity, in the dissemination of Buddhism in the Middle Ages, in the modernisation of Buddhism in the contemporary West, and now in the integration of Buddhist ethics with modern social life.

Yet, the deepest aspect of the topic of women in Buddhism is not a matter of social justice, but rather of the liberation and happiness of all beings. Whether this is facilitated within an organized religion like Buddhism, or in secular social ethics, men and women must work together to create a more equitable world for all.