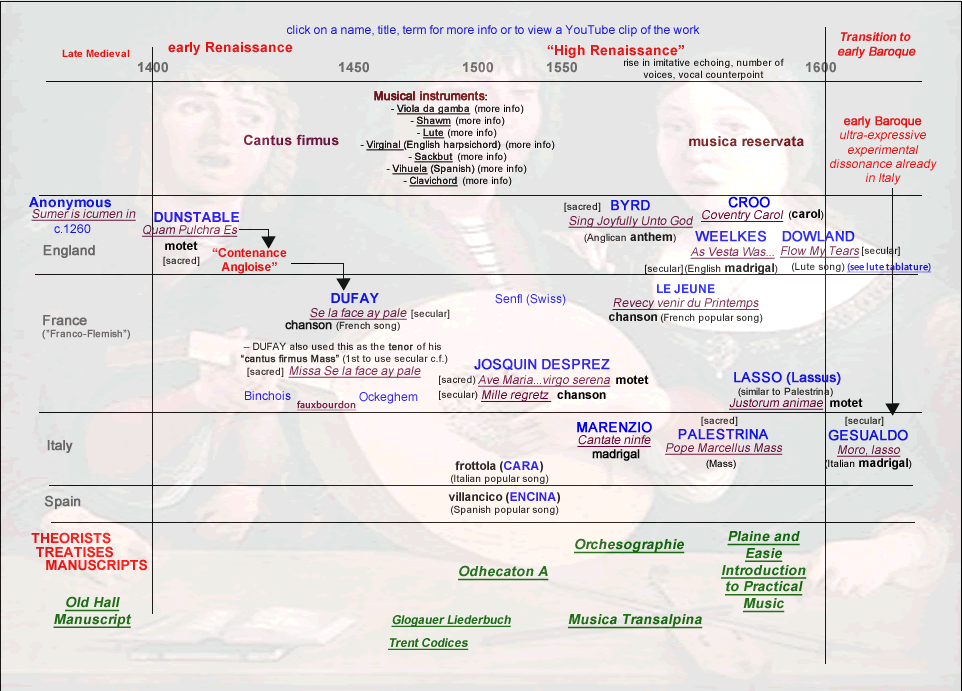

Renaissance Music: A Period of Musical Innovation

The Renaissance was an era of rebirth, and a fresh spirit of innovation characterized the musical landscape.

The Renaissance was an era of rebirth, and a fresh spirit of innovation characterized the musical landscape.

Table of Contents

ToggleThe Renaissance was a period when study, trade, exploring the New World, scientific discovery, and magnificent creative achievement all underwent a rebirth. Although Renaissance artists and philosophers were as religious as those of the Medieval Era, they sought to reconcile theological practice with the new spirit of scientific inquiry.

The Protestant Reformation, which began in Wittenberg in 1517 when Martin Luther nailed his 95 theses disputing the Catholic Church’s teachings to the church door (this may me a tad overdramatic), culminated in the founding of the Lutheran denomination. The Reformation had a significant impact on Renaissance music as well.

Throughout the Reformation, new churches gave birth to new religious music styles. With plenty of turbulence in the church landscape, secular music began to compete with its sacred counterpart.

The Church controlled music throughout the Middle Ages. Most of the compositions were created for religious use. Pieces were based on simple chants, which had been used in worship from the early days of Christianity. Although most of the music continued to be religious during the Renaissance, the Church’s political control over society had loosened, allowing composers greater liberty to be influenced by art, classical mythology, and even astronomy and mathematics. For the first time, music could be published and spread thanks to the advent of the printing press.

The Latin Mass, notably that of Josquin des Prez, is possibly the most essential kind of Renaissance music.

The majority of music composed during this period was designed to be sung, either as massive choral works in church or as songs or madrigals. However, through polyphonic imitation (where another voice part or instrument echoes a musical idea), composers began expressing feelings through word painting, also known as musica reservata, musical symbolism expressing thoughts present in the text. Madrigals were especially popular for expressing feelings of love, loss, and the like.

On the other hand, instrumental music blossomed as technology permitted musical instruments to become more expressive and allow a more dynamic range (loud and soft). In addition, composers could now compose pieces for solo instruments such as the sackbut and lute.

Musically, the Renaissance represents expanded expressiveness and more distinct composing styles. Therefore, Renaissance music sounds richer and more ‘complete’ than Medieval music. At least five, sometimes six, separate vocal parts with extended ranges (higher soprano parts, lower bass parts) are common in Renaissance compositions.

In contrast to the Medieval method of successive composition — the chant line was predetermined, composers constructed the upper melody next, and the inner voices were filled in last. Instead, Renaissance composers began to write in a new way called simultaneous composition — composers constructed all the voice parts together phrase-by-phrase.

Phrase-by-phrase composition allowed composers to develop polyphonic imitation, where the music becomes a ‘conversation’ and is passed from voice to voice (instrumental or vocal). Composers also started employing cadences which are conclusive phrases or section endings akin to spoken or written language.

The intervals of a third and sixth, considered dissonant in the medieval period, rose to prominence in the Renaissance. It opened new sound colors and allowed composers to expand their metaphorical compositional toolbox.

In 1455, Gutenberg used his press to create a Bible edition; this Bible is the oldest complete existing book in the West and one of the earliest books printed from movable type. Gutenberg’s wooden press remained dominant for more than 300 years, printing at a constant rate of 250 pages per hour on one side. The printing press revolutionized how people spread information across the Continent and led to a higher level of literacy.

Most composers in the early Renaissance were from Northern France or the Low Countries (the Franco-Flemish School), where the courts were incredibly supportive of the arts. Later, when the Italian city-state system reached its zenith, the attention shifted beyond the Alps. As a result, many northern musicians moved south to seek their fame and fortunes.

Italian composers began to appear and dominate the music scene as well. Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli composed great works for large choirs and ensembles of instruments in St Mark’s Basilica in Venice. Allegri (perhaps his most famous composition – Miserere) and Palestrina were Rome’s last great Renaissance composers, creating massive, flowing choral works that still captivate the ears.

We’ll approach the music landscape by country, starting with England, moving across the channel to France and the Low Countries, briefly crossing over into Germany, continuing to Spain, and finally looking at Italy. We’ll look at notable composers, works, and developments and what role each played in the music of the Renaissance. While the results are divided into individual countries, they were not isolated events but a finely woven tapestry of cross-fertilization of ideas, events, and innovations.

While France may have led the music scene in the Middle Ages and England looked to the Continent for inspiration, a new sound was emerging known as the contenance angloise. In the early Renaissance, it was England’s turn to be a significant player and (re)determine the course of Western classical music.

The term contenance angloise (‘the English countenance’) refers to the style of music composers on the Continent used to describe and associate with English composers such as Leonel Power (ca. 1370/85–1445) and John Dunstable (ca. 1390–1453). Power and Dunstable are regarded as the fathers of the development of all classical music across Europe when musical cross-fertilization between the Continent and England was at its height.

The English style of music exemplified richer sonority, using chords and chord progressions in a more ‘natural’ way by approaching and resolving discords (‘false sounds’) in a more refined manner. Vocal lines sounded more lyrical, and composers gave the voices equal importance. The music sounded different from the late Medieval music because it had a richer, fuller harmony.

Dunstable’s three-part motet, Quan pulchra es (video), is often cited as exemplifying the English sound. Two more examples include Dunstable’s motet Veni sancte spiritus (video) from the Old Hall Manuscript, and Power’s sacred music (video). Power is the most represented composer in the Old Hall Manuscript.

The Protestant Reformation, sparked in 1517 by Martin Luther in Germany, spread throughout the Continent and reached England. One of the most important manuscripts from the time is the Old Hall Manuscript which contains 148 polyphonic works from English composers and is the most critical source of sacred music in England from the 14th and 15th centuries. The manuscript survived the English Reformation when Henry VIII dissolved Roman Catholic churches and monasteries and seized their possessions around 1539.

In England, music served the monarchy’s political and the church’s sacred purposes, depending on the ruling monarch. Under Henry VIII, music remained true to its Catholic roots. Still, under Edward VI (r. 1547–53), it swung back to Protestant doctrines, and English replaced Latin in the services. Under Mary (r. 1553–158), Edward VI’s half-sister, the liturgy returned to Catholic worship.

Elizabeth I (r. 1558–1603) again broke with the papacy and returned to Edward VI’s liturgical reforms (Protestantism), yet she allowed Catholics to hold their services in private and had them swear allegiance to her as monarch. She sought a middle road and incorporated elements from both Catholic and Protestant in the Anglican Church. Elizabeth I also allowed for the use of Latin hymns, responses, and motets in her court to serve her political needs when she received international diplomats from hostile, Catholic-dominated Europe.

In the English protestant churches, the anthem developed as a musical form for church services as opposed to Roman Catholic motets. It is a choral composition with a sacred Latin text usually sung by the choir near the end of Evensong or Matins.

At first, unaccompanied choral anthems were the norm and were called full anthems and composed in a contrapuntal style (counterpoint is the combining two or more independent voices to make an intricate polyphonic musical texture). However, the emergence of the verse anthem (which employed a solo vocal part and later several soloists as well as a chorus) in the 16th century promoted the use of musical accompaniment, either by the organ or by instrumental ensembles such as wind instruments or viols.

William Byrd (ca. 1540–1623) stands out as a Catholic who composed music for the Anglican services and Latin masses and motets. He uses imitative techniques (from the Continent) where one voice succeeds the other and is sometimes interspersed with homophonic declamation where all the voices move together from note to note, singing the exact text. To learn more about the fraught relationship between Catholics and Protestants and about Byrd’s time and music, have a look at this documentary (video).

Of course, the motet was still present, as mentioned earlier. One of the best examples of a polychoral (more than one choir singing together) motet is Spem in alium by Thomas Tallis (ca. 1505–1585). Tallis was possibly Byrd’s teacher and a contemporary whose career overlapped with Byrd’s. They were also awarded an exclusive license to publish and print music in England, despite both being Catholics and Byrd’s somewhat fraught relationship with the Anglican church.

Tallis’s forty-part motet Spem in alium (video) may have been a challenge he set himself or after, presumably the Duke of Norfolk, heard Alessandro Striggio’s motet Ecce beatam lucem (video), a forty-part choral piece. Scholars believe the first performance took place in private at Arundel House, London, in 1570 or 1571 because Tallis was also a Catholic.

Another popular form of religious music in England was the carol — a religious poem set to two or three parts in a popular style and often with a soloist and choir alternating portions of the text. The most famous example from this period is the Coventry Carol (video) which was part of a mystery play based on the second chapter of the Gospel of Matthew. The play, The Pageant of the Shearmen and Tailors, depicts the massacre of innocent male babies in Bethlehem as ordered by King Herod. It is in the form of a lullaby sung by a mother to her doomed children.

While it is uncertain who composed the music, the text was written by Thomas Croo around 1534, and the music was composed around 1591. Of interest are the last two chords of the carol, which moves from a minor (sad) key to end on a major (happy) chord — this device is known as the Tierce de Picardie or Picardy third. The Picardy Third is an expressive device, perhaps even showing the listener that hope is always around the corner.

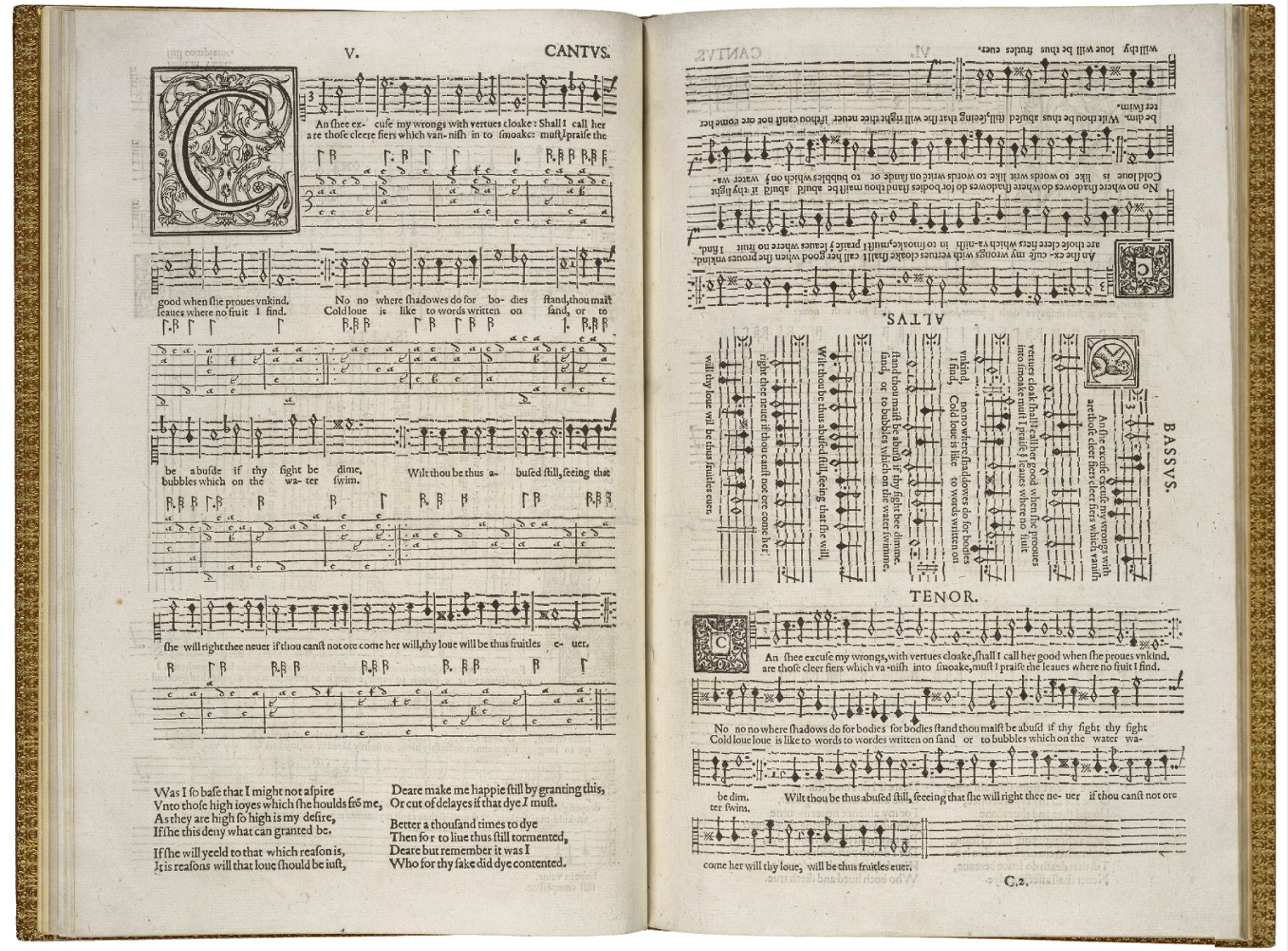

Tablature is a notational system that tells the player which string to pluck and where to place the finger instead of sheet music. Four singers may sing with lute accompaniment or without, and the music is arranged so they can sing from the same book at one table.

Secular music also thrived during this period in England. A notable English renaissance composer is John Dowland (1563–1626). He composed numerous secular madrigals and songs for the lute. Some of his work includes Lachrimae (video), Flow my tears (video), and Come again (video). Dowland is known for his exquisitely sad compositions with texts and music focusing on unrequited love – Elizabethan poetry was somewhat painful and cynical regarding the affairs of the heart.

Another composer, Thomas Morley (1557/8–1638), was a prolific composer of madrigals, canzonettes, and balletts (borrowed from the Italian canzonetta and balletto). He also wrote a book, A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke (1597), aimed at the broad public as an instruction manual and invitation to the amateur to pick it up and learn about music.

More interestingly, Thomas Weelkes’ madrigal, As Vesta was (video), has a text and music set by the composer himself. The text provided him with ample opportunity for word painting, for example rising and descending scales set to ‘ascending’ and ‘descending’ and one, two, three, or all voices to coincide with words like ‘alone,’ ‘two by two,’ ‘three by three,’ and ‘together,’ respectively. The motet illustrates another compositional figure, where the phrase ‘Long live Oriana’ (a nickname for Elizabeth I) is set fifty times in several transpositions to include a vast number of nations symbolically.

Texts from this period sometimes used bawdy themes, and surprised their listeners with rather ‘interesting’ madrigals filled with sexual innuendo or commenting on society and their vices. An example is a madrigal composed on the name of famous architect Inigo Jones – the proper name is changed to syllables and, consequently, a verb: In – I – Go, Jones (audio).

The area we know today, covered by the northeastern corner of France, Belgium, and Luxembourg, can be regarded as the powerhouse of European music during the 15th and 16th centuries. In this region, ars nova played an important role in the Middle Ages. However, the English and Italian musical inspiration soon replaced it — the first played a role during the first part of the Renaissance (ca. 1400–1500) and the latter during the second half (ca. 1500–1600, the ‘High Renaissance’).

Guillaume Dufay (ca. 1400–1474) received his musical instruction as a chorister at Cambrai Cathedral. Early in his life, he began demonstrating tremendous promise as a singer and composer.

As an adult, Guillaume Dufay was summoned to Italy, first to the Court of Malatesta in Rimini and Pesaro and afterward to the Papal Choir in Rome and the Court of Louis of Savoy in Geneva. In 1436, he was in the service of Pope Eugene IV in Florence, where he composed songs for the consecration of Brunelleschi’s completed dome in Florence. He regularly returned to Burgundy and subsequently held canonries at Cambrai, where he lived for the remainder of his life until he died in 1474.

Dufay traveled widely throughout the Continent and absorbed influences from other composers but also influenced others. In his chansons (a song for several voices, sometimes accompanied by instruments), he amalgamates French and other international influences. An example is Revellies vous (video) from 1423, which was composed to celebrate his patron’s wedding at the court of Rimini and Pesaro. The Italian characteristics of this piece include relatively smooth vocal lines, melismas (one syllable sung to a group of notes) on the last syllable of each line of text, and a change in meter (changing from compound 6/8-time to simple 3/4-time). French elements include the ballade form, long melismas, free dissonances (notes that sound ‘wrong’), and free syncopation. Another often-quoted example is his ballade Se la face ay pale (video) from ten years later (ca. 1433), written while he was at the court of Savoy.

Dufay would always hold religious music in high regard. As he grew older, he composed increasingly more religious music such as motets, chant settings, and polyphonic mass settings. A technique that Dunstable and his contemporaries used in England, which Dufay adopted, was the faux bourdon (‘false bass’) — a musical texture created through three voices in parallel motion (moving together), a third and a sixth apart. In the English faburden, the melody was featured in the lower voice, and the two upper singers (descant) improvised on the lower voice’s melody with their thirds and sixths.

Dufay’s notable religious compositions include his motets. For example, his setting of the hymn Christe, redemptor omnium (video), uses fauxbourdon as it paraphrases the chant on thigh it is based. Another example is his motet, Nuper rosarium Flores (video), composed for the benediction of Bunelleschi’s dome for the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore on March 25, 1436, in Florence. A prime example of Dufay’s late style is Missa l’homme armé (video), based on a secular tune of the same name. The secular song L’homme armé (The Armed Man) forms the cantus firmus upon which the mass is based. The cantus firmus originates in the medieval organum (where voices are on top of an existing chant melody or vox principalis). We could also take this a step further and say that the fauxbourdon technique is a type of precursor to the cantus firmus or even developed into it when it is used in secular or sacred compositions.

Dufay was not the only composer who stood out during this time. Still, he was undoubtedly revered by his contemporaries and future generations. Dufay drew all the international influences around him into his compositions, which inspired his contemporaries and composers that followed during the High Renaissance.

Gilles de Binche (c. 1400–1460), known by his coined name, Gilles Binchois, was a contemporary of Dufay. He was the organist at Sainte-Waudru Cathedral, Mons, Belgium, between ca. 1419 and 1423. After that, he was employed by the Duke of Suffolk in Paris (1424/5) and may have traveled with him to England. He served as chaplain at the Court of Burgundy from 1431 to 1453. He was also a canon at a church in Mons alongside Dufay, whom he probably met in middle age.

Binchois and Dufay maintained the softly delicate rhythm, suavely exquisite melody, and seamless control of dissonance of their English contemporaries in both their sacred and secular compositions. The words to several of his songs (chansons) were written by well-known writers of the day, most notably Charles, duc d’Orléans, and Christine de Pisan. His music, notably his chansons, was famous and has been shown to inspire works by other composers. His notable works to listen to include his rondeau De plus en plus (video) and his sacred choral works (video).

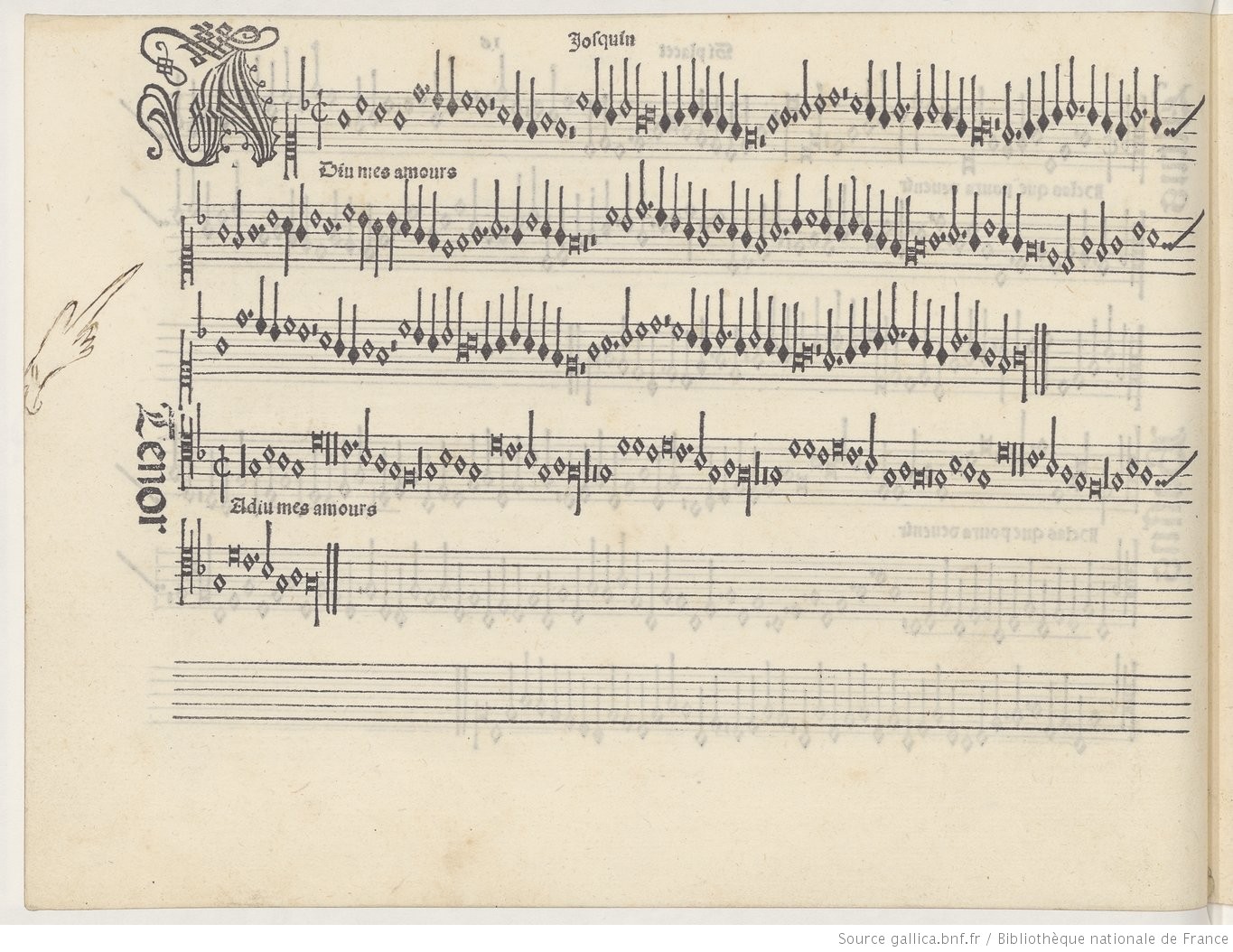

Josquin des Prez (ca. 1450/55–1521) devised a sophisticated method of expressive — and frequently imitational — movement between several voices (polyphony), building on the work of his forebears Guillaume Dufay and Johannes Ockeghem. He put more emphasis on the connection between text and music, departing from the early Renaissance style of long, monosyllabic melismatic lines in favor of shorter, repeated patterns between voices. Josquin was a singer, hence the majority of his works feature singing.

Josquin perfected Renaissance polyphony. He was the most extraordinary counterpoint (pre-Bach) innovator and invented melodic imitation between voices in choral composition. His contributions in these areas helped to steer the later Renaissance and produce new secular and sacred music forms that broke with homophonic medieval norms.

The development of printing enabled the widespread distribution of Josquin’s work, which contributed to his influence. Josquin’s pieces, a particular favorite of printer Petrucci, were chosen to start significant anthologies and include a single composer’s earliest printed surviving music collection. As a result, the skills of Josquin were highly valued across Europe. His reputation survived when polyphonic music fell out of vogue in the Baroque era. He is still regarded as one of the most influential Renaissance composers. His most notable works include Misere mei deus (video, motet), Missa l’homme de armé (video, mass), and Ave Maria, Virgo serena (video, motet).

The printing press (video) revolutionized how information spread across the Continent. Instead of painstakingly copying manuscripts by hand, pamphlets, tracts, books, and sheet music could be printed much faster and shared more easily.

In 1439, the first reference of a mechanical printing press in Europe emerged in a lawsuit in Strasbourg, revealing the creation of a press for Johannes Gutenberg and his collaborators. Gutenberg’s movable type press and others of its age in Europe owed a lot to the medieval paper press, which was based on the old wine-and-olive press of the Mediterranean region. Turning a big wooden screw with a long handle applied downward pressure to the paper, which was spread over the type fixed on a wooden platen. In 1455, Gutenberg used his press to create a Bible edition. The Gutenberg Bible is the oldest entirely existing book in the West and one of the earliest books printed from movable type.

The printing press also meant printers could print music, reach all the corners of the Continent, and travel with priests to the New World on missionary work.

Martin Luther (1483–1546) is seen as the main instigator of the Protestant Reformation when he nailed his 95 theses to the church door in Wittenberg on October 31, 1517 (this might not have actually happened). He approached religion with a humanistic viewpoint which taught him to rely on reason, direct experience, and his reading of scripture rather than receive authority as proclaimed by the Pope and Roman Catholic Church.

Luther was a singer and played the lute and flute. As a composer, he greatly admired the Franco-Flemish polyphony, especially the works of Josquin des Prez. He followed in the footsteps of ancient Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle, who believed music had educational and ethical power. Additionally, he believed that when a congregation sang together in their vernacular tongue, they could unite in proclaiming their faith and praising God — unlike the Catholic churches where only the choir sang.

The most significant development from the Reformation is the Lutheran chorale. Composers, including Luther, worked quickly to compose suitable music (video) for church services. There were four primary sources for chorales:

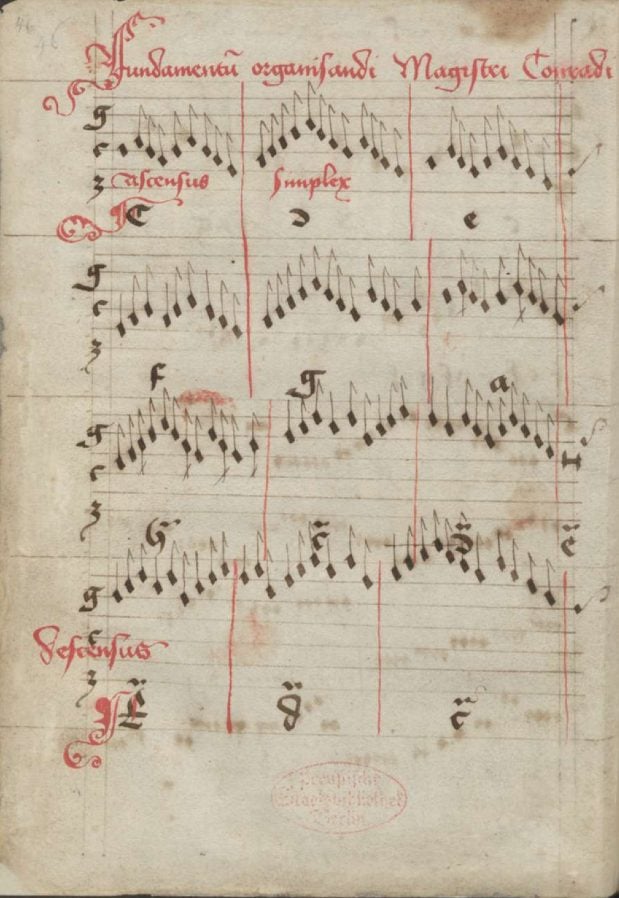

German music was significantly influenced by worldwide repertory. It was working to establish its own musical language in the fifteenth century. This is demonstrated by several manuscripts, including the Emmeram Codex, the Lochamer Songbook (video playlist), and the seven Trent codices, all of which include a significant amount of works with Burgundian, Italian, and English roots.

Another way composers tried to learn this ‘foreign art’ was through contrafacta, when the original music is presented with a new text underlay. For example, the Nuremberg-born Conrad Paumann (c. 1410–1473) created the organ tablatures for Dufay’s compositions, and the Tyrolean Knight Oswald von Wolkenstein (c. 1376–1445) produced vocal music in French and Italian with a German text. The country excelled in instrumental music, although most German music relied on incorporating foreign elements into the vocal melody.

Paul Hofhaimer (1459–1537) held a role at the Court of Emperor Maximilian I, who granted him the title Knight in 1515, among other positions. Hofhaimer, a performing musician and the instructor of a whole generation of German organists, had such a profound musical impact that his pupils were referred to as ‘Paulomines.’

Witnesses attested to Hofhaimer’s extraordinary talent as an improvisation. He could perform for hours without repeating himself. The renowned school of German organists of the Baroque era can be traced mainly to Hofhaimer. Additionally, several organists he taught later moved to Italy, such as Dionisio Memno, who took a position as organist at St. Mark’s in Venice and taught the early Venetian school organists there, Hofhaimer’s approach.

His period-appropriate German Lieder is often in bar form with a polyphonic first section and a more chordal second section. He rarely employed the seamless polyphonic texture that Franco-Flemish composers like Josquin or Gombert were then developing. Additionally well known as an organ consultant, Hofhaimer routinely guided builders on the development and upkeep of organs.

The compositions of the Flanders-born Heinrich Isaac (ca. 1450/1455–1517) and his pupil, the Swiss composer Ludwig Senfl (ca. 1490-1543), would be the pinnacle of these so-called tenor songs. Senfl’s Ach Elslein (video) is a well-known piece transcribed in many books and manuscripts, as well as in musical arrangements.

Orlande de Lassus (1532–1594) was one of the most versatile, universal, and prolific composers in the High Renaissance. He wrote over 2,000 vocal works in French, Latin, Italian, and German during his lifetime. It is curious to note that no purely instrumental pieces of his survived, especially when instrumental music became increasingly popular as a vehicle of expression across the Continent. He was primarily known as an advocate of emotional expression and depicting the text through music. Although his output is vast, listening highlights from his oeuvre include the motet Cum essem par value (video), the mass Douce mémoire (video), and Les Lamentations de Job (video).

While Dufay synthesized the international styles found across the Continent during the early Renaissance, Lassus assimilated all the primary forms of music in his works, incorporated the musical styles from across Europe, and was one the most regarded and revered composers throughout the Continent during the High Renaissance.

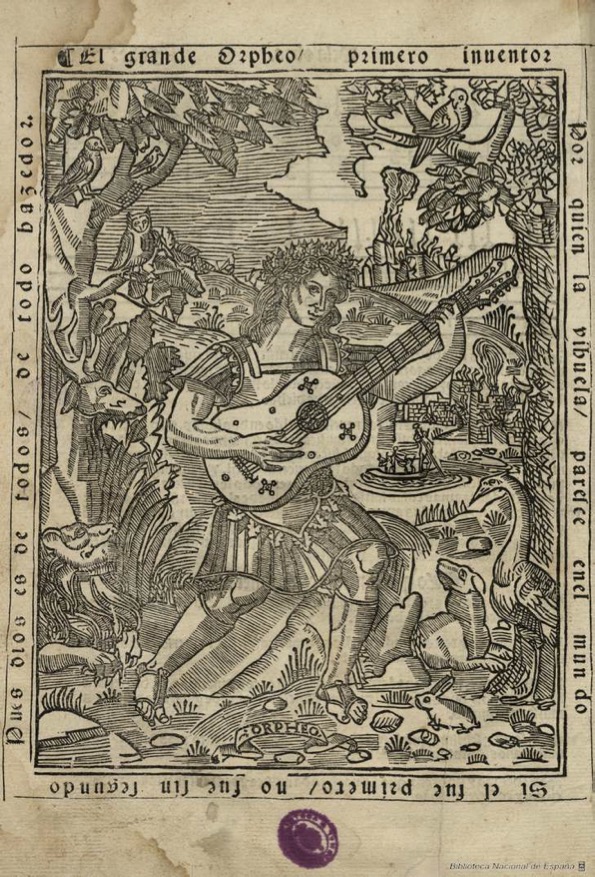

In 16th-century Spain, the long reigns of Kings Charles V (1517–1556) and Philip II (1556–1596) created stability in the nation, resulting in the aesthetic and musical blossoming of national culture. Spanish religious music was also in lockstep with the music found in Rome.

Iberian composers attained the highest level of perfection in music, and many top-notch musicians were there. The seven vihuelistas (vihuela players) — Milán, Narváez, Mudarra, Valderrabano, Pisador, Fuenllana, and Daza — were the most significant. They all released their volumes of compositions on the vihuela, a guitar-shaped instrument. Players played the vihuela like the lute between the years 1536 and 1576.

Most of the instrumental selections in these seven books for solo vihuela are fantasias, which, in Milán’s words, are so termed because ‘they proceed solely from the author’s fancy’ and are not bound by any particular form. Another popular style was the difference, or variation, typically based on an aural pattern or a melody from well-known songs like Guardame las vegas (video) or Conde Claros (video) — both examples by Narváez.

More minor compositions like the tanto, comparable to a prelude, and the soneto, a brief piece likely inspired by a well-known song or theme, also commonly appear. Unfortunately, manuscript sources are less common than printed ones. Still, some, like the Simancas fragments, contain a few uncommon instances of dance music, such as the Pavanilla and La Moreda. Notable recordings to listen to include Luys Milán’s Fantasias I–VI (video) from El Maestro Vihuela, his Pavana and Gallarda (video), and this compilation of works (video) by Luys de Narváez.

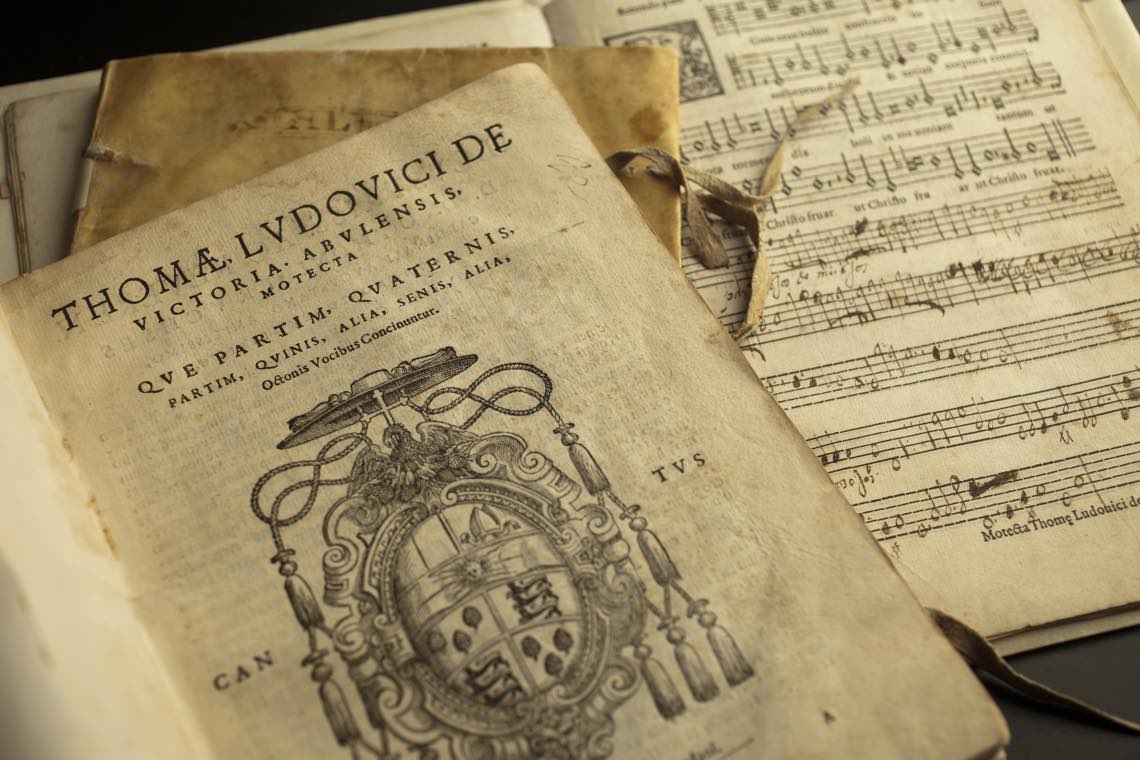

The most significant Counter-Reformation composer in Spain is Tomás Luis de Victoria, who also made a name for himself as a revered composer of religious music in the late Renaissance. Victoria’s music passionately expressed Spanish mysticism and faith.

Padre Martini (1706–1784) a music historian and a mentor to Mozart also commended Victoria for his joyous innovations and melodious language. Other reviewers find in his work a mystical intensity and a direct emotional appeal. His notable works to listen to include Missa Alma Redemptoris (video, eight-voice mass) and Ave Maria (video, eight-voice motet).

While Italy did not make significant contributions to the field of music during the Middle Ages’ ars antiqua, they excelled in the madrigal. Printing polyphonic music began in Venice and helped to cement the reputation of the Burgundian School of Franco-Flemish composers all over Europe.

The beginning of the sixteenth century saw several significant innovations in European music. In 1501, a Venetian printer, Ottaviano Petrucci, produced the Harmonice Musices, the first notable polyphonic printed music (video) collection known as Odhecaton A. Petrucci’s success paved the way for music printing in France, Germany, England, and other countries. Before 1501, all music had to be transcribed by hand or taught by ear. In addition, religious institutions or wealthy courts and homes only held music books. While these books were costly after Petrucci, it became feasible for many individuals to purchase them and learn to read music.

Petrucci’s approach was a careful three-pass procedure. The staves (the lines and spaces) would be pressed into the paper first, followed by the notes and musical symbols in a second pass. Finally, on the third pass, the printer could insert the text. The final product is one of the most outstanding examples of musical printing from the early 16th century.

Three other significant developments took place in Italy during the Renaissance — the rise of the madrigal, polychoral singing at St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice, and the Council of Trent’s instructions to simplify music.

The polychoral style emerged in Northern Italian churches in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It proved an excellent fit for the architectural quirks of Venice’s massive Basilica San Marco di Venezia. Antiphonal music was written by composers such as Adrian Willaert, the maestro di cappella of St. Mark’s in the 1540s, in which opposing choirs sang successive, often contrasting phrases of the music from opposing choir lofts, specially constructed wooden platforms, and the octagonal bigonzo across from the pulpit. This is a rare but fascinating example of a single building’s architectural oddities fostering the spread of a style that had grown popular throughout Europe and helped define the transition from the Renaissance to the Baroque era.

Giovanni Gabrieli (ca. 1554/1557–1612) was a composer, organist, and one of the most influential musicians of his period. The polychoral style reached its apex in the late 1580s and early 1590s, when Giovanni Gabrieli was the organist and prominent composer at San Marco and Gioseffo Zarlino was still maestro di cappella. Gabrieli appears to have been among the first to identify instruments in his published works, including enormous choirs of cornetti and sackbuts; he also seems to have been among the first to describe dynamics (as in his Sonata pian’ e forte, video) and to establish the ‘echo’ effects for which he became famous. At this time, the stunning, thunderous music of San Marco had spread throughout Europe, and many musicians flocked to Venice to hear, study, absorb, and carry back to their nations what they had learned.

The Council of Trent, held between 1545 and 1563, was called by the Roman Catholic Church to address the heresies the Protestant Reformation espoused and the Church’s clarifications on doctrines and teachings.

The Council was especially harsh on polyphonic music, in which each vocal part had its own melody because it made the words nearly hard to interpret. Such music is lovely, yet it was seen to undermine the purpose of the religious service.

The Council of Trent briefly contemplated outlawing polyphonic music but finally decided against it, instead imposing strict guidelines for how composers created such pieces. They asked that church music be serious and controlled, avoiding the dazzling excesses of ‘amusement music’ (secular), and that the text be constantly understandable. They favored syllabic styles, in which each pitch corresponds to a single syllable of text, and homorhythmic forms, in which all voices move in rhythm together, singing the exact text simultaneously.

Fortunately for the Catholic Church, a composer was eager to take on the task of crafting engaging music that fulfilled their specifications. Giovanni da Palestrina (1525–1594) worked for the Catholic Church his entire life. He worked as an organist, vocalist, and choir director at several churches in Rome, including St. Peter’s Basilica. Unfortunately, women were not permitted to sing in the choir at St. Peter’s. Instead, the high vocal parts were sung by boys, men who sang in a high falsetto range, or males known as castrati because they had been castrated before puberty, and so kept soprano voices.

The Missa Papae Marcelli (video) was, therefore, a direct answer to the Pope’s protest and a more general response to concerns the Council of Trent raised later. By the time it was published in 1567, it had become a model for Catholic composers worldwide. Palestrina met the new standards of the Catholic Church with Pope Marcellus Mass while remaining true to his artistic principles. His Mass was beautiful and dramatic, but it was also humble and straightforward. As a result, he successfully created art that fulfilled the needs of worship.

The frottola (plural frottole) was the most popular secular Italian song genre in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. It was the most significant and ubiquitous forerunner of the madrigal. The era from 1470 to 1530 saw the most activity in the creation of the frottole, following which the madrigal took its place.

There is very little information available concerning performance practice. Contemporary versions are sometimes for many voices, with or without lute tablature; keyboard scores are occasionally preserved. Frottole may have been sung as a single voice with lute accompaniment. Marchetto Cara (ca. 1465–ca. 1525) may have done so at the Gonzaga court, as his reputation as a lutenist, singer, and composer of frottole suggests.

Lastly, the madrigal was the most important secular genre in the Renaissance. The madrigal and its offshoots, like French chansons, German Lieder, and English madrigals, served as laboratories for experimenting with the expression, declamation, and depiction of words. This exemplifies the growing influence of Humanism as it spread across Europe.

Early madrigalists from around the 1520s took their cue from the frottola. They were usually in four voices, homophonic, and with line endings marked by leisurely cadences (musical endings). Philippe Verdelot (1475–1552) is considered the father of the Italian madrigal. He is known for his 1530 collection, Madrigali de diversi musici: libro primo de la Serena.

One of the most famous early madrigals, Il bianco e dolce cigno (video), by Jacques Arcadelt (1507–1568), shows signs of mixing homophony with imitation. He probably combined his teachings from the Franco-Flemish School with the Italian madrigal because he was active in France and Italy.

Cipriano de Rore (sometimes Cypriano) (1515 or 1516–1565) was an Italian Renaissance composer of Franco-Flemish origin. He was not only a significant representative of the group of Franco-Flemish composers who traveled to live and work in Italy following Josquin des Prez. He was also one of the most influential composers of madrigals in the middle of the 16th century. His experimental nature, chromatic, and very expressive approach significantly impacted the evolution of that popular form.

We may trace all lines of growth in the madrigal in the late sixteenth century back to concepts first seen in Rore’s madrigals; his only genuine spiritual successor was another innovator, Claudio Monteverdi. Rore’s religious music, on the other hand, was more backward-looking, demonstrating his link to his Netherlandish roots. His masses, for example, are evocative of Josquin des Prez’s work.

Giovanni de Macque (ca. 1545–1614) deserves special mention for several reasons. First, he was a Franco-Flemish composer living and working in Naples, possibly influenced Carlos Gesualdo’s chromaticism (or picked up the idea from him), and a prolific madrigal composer who published twelve volumes. He spent much of his life in Italy, first in Rome in 1568 and then in Naples from around 1585–1590. He left shortly before Carlos Gesualdo’s infamous murders. Apart from his madrigals, he also composed one volume of motets and numerous books of keyboard music — the latter of which combined a boldness of modulation (as in Consonanze extravagant, video) with contrapuntal resource from his northern upbringing in inventive toccata and canzona movements. Finally, he was the most notable Franco-Flemish madrigalist working in southern Italy.

Carlos Gesualdo perhaps offers one of the most intriguing biographies of all composers. His music (video) became increasingly chromatic, reminding us of music we would only find again in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Gesualdo offers a rare perspective into a tortured mind — it may be disturbing to explore this side of the human psyche, but the human experience is made up of lows and highs. He offers us a look into the darker side of human existence, without which we cannot enjoy the delights of human existence.

Given the limitations of many sources and the apparent bias against women it is tempting to imagine that female musicians were a rarity. After all, male composers dominated the Renaissance landscape, and any musical institutions were exclusively for males, making it difficult or impossible for women to become professional musicians. Cultural expectations greatly hindered a woman’s capacity to pursue a career dominated by men, as demonstrated throughout history. Gender and social status dictated the female experience, with the notion that a woman’s life should be limited to marriage, childbirth, and home administration.

Writing and creating music at home or in court was considered a limited activity for women. A feeling of respectability likely discouraged women from exposing such a pleasure. Even in church, girls and women were not allowed to sing, and the musical instruction gained by choirboys was unavailable to girls. Singing was only an acceptable activity for women in abbeys and monasteries.

Music composed by female composers is just as beautiful and proficient as you could ever expect. For example, the madrigal Morir non può il mio cuore (video) by Maddalena Casulana (ca. 1544 – ca. 1590) and one by Vittoria Alleotti (c. 1575 – after 1620) Io v’amo vita mia (video).

Michael Praetorius’s (1571–1621) Syntagma Musicum — a book on instruments — was published in 1618 at Wolfenbüttel, northern Germany. It was the second volume of a three-volume encyclopedia. While this may appear ‘late’ for a piece about Renaissance instruments, Praetorius provides an authoritative look at the instruments used during the Renaissance.

Praetorius shows that single-line instruments — playing just one note at a time — were typically performed in consorts or groups of similar instruments of various sizes. This shows a shift in taste from the late Medieval era when ensembles of different instruments appeared to be appreciated. The transition is undoubtedly due to the contrapuntal character of much Renaissance music, in which each section is of equal significance and best portrayed as part of a homogenous tapestry. The traditional ensemble featured three voices early in the Renaissance, expanding to five or six by the end of the 16th century. The Renaissance also witnessed the emergence of a significant and virtuoso solo repertoire for keyboard instruments, lutes, and the like.

This list of instruments is by no means exhaustive but highlights instruments that came into their own right during the Renaissance from the Middle Ages.

Praetorius was an organist by trade, ergo, organs receive special attention in his work. Despite various national variations, the ordinary Renaissance church organ comprised one or two manuals (rarely three), a pedalboard, and roughly ten stops, occasionally including the earliest metal reeds.

The clavichord was a popular keyboard instrument during the Renaissance period. Praetorius recommends it for beginner keyboard players since it was so simple to tune and did not have the harpsichord’s problem with broken quills. Clavichords of the Renaissance were of the ‘fretted’ variety, which meant that each string could generate three or four distinct pitches by being hit in different locations by metal tangents attached to the three or four matching keys. Instrument makers kept the number of strings required to a minimum, but it also meant that players could not play some pitches simultaneously since they utilized the same string, resulting in a distinctive, disconnected articulation. The clavichord’s true advantage was expressiveness: it was the only keyboard instrument in regular use that could generate gradations of loud and soft and even vibrato with the touch of the player’s finger.

The harpsichord, virginals, and spinet were all plucked-string keyboard instruments popular throughout the Renaissance. The first mention of a harpsichord-like instrument is in a book written around 1440 by Henri Arnaut de Zwolle, although the earliest surviving examples date from the early 16th century. Today, we usually reserve the word harpsichord for those that resemble a grand piano. This fundamental design may be seen in many Italian instruments, however, they are often more thin and angular. They are also significantly lighter in weight than pianos (and much lighter than other harpsichords) and were frequently housed in special exterior cases for protection and adornment.

The name sackbut is most likely derived from the old French verbs sacquer and bouter, which characterize the player’s pulling and pushing arm movements. From its initial appearance in the mid-15th century, the Italian term for it was always trombone — we merely use sackbut now to distinguish it from its contemporary version. The sackbut has altered the least of any instrument in general use today, evolving fast from the single-slide instrument, the slide trumpet. Its first appearance in an ensemble appears to have been as a regular member of the shawm band.

The lute progressed from five courses (or pairs of strings) in the early Renaissance to seven, eight, or even ten strings by the late Renaissance. As the number of strings increased, the player’s arm began to come over the lute’s shoulder. The thumb came out, as in the current guitar technique. Lutes were among the first instruments to acquire a solo repertoire. Still, it was also expected that by the middle of the 16th century, they would join in ensembles with other instruments as a form of proto-continuo. Later in the Renaissance, artisans created lutes with expanded necks called archlutes, theorbos, or chitarrones. The bigger ones were usually single-strung and not double-strung and valued as accompaniment instruments.

The Renaissance violin has a shorter, stubbier neck and a few minor variations from the modern instrument. It is easily distinguished in both look and sound. The bow was most likely handled with the thumb on the hair, as it was in France until the 18th century. Recent research has revealed that the violin, mainly when played in a violin consort with other violin family members, was highly esteemed at the courts of England and France. Because so much great violin-making appears to have been based in Italy, even throughout the Renaissance, the violin might have also been significant there. Andrea Amati (1525–1611), for example, started creating violins in the mid-16th century. We frequently conceive of violins as descended from viols, yet they appear to have been different families that evolved concurrently. The violin may have come from the Lira da braccio, but by the middle of the 16th century, it had taken on its current form.

In the Renaissance, music was essential to civic, ecclesiastical, and courtly life. The productive exchange of ideas in Europe, as well as political, economic, and religious events from 1400 to 1600, resulted in significant changes in composing techniques, ways of transmitting music, new musical genres, and the invention of musical instruments. The most considerable portion of the music of the early Renaissance was written for church use — polyphonic masses and motets in Latin for prominent churches and palace chapels. However, by the end of the sixteenth century, patronage had expanded to encompass the Catholic Church, Protestant churches and courts, affluent amateurs, and music printing — all of which provided an income for composers.

The Renaissance humanists examined ancient Greek treatises on music, which emphasized the vital link between music and poetry and how music may elicit emotional responses from the listener. Inspired by the ancient culture, Renaissance composers combined poetry and music in more dramatic ways, as witnessed in the development of the Italian madrigal, but even more so in the Continent’s adoption and further experimentation and exploration of the English Sound as found in the works of Dunstable, Dufay, Josquin, Victoria, and Lassus to name a few.