What Is Comparative Literature and Why Study It?

Comparative Literature is an academic discipline that pursues connections between diverse cultural contexts.

Comparative Literature is an academic discipline that pursues connections between diverse cultural contexts.

Table of Contents

ToggleOnce upon a time, there was a…

Sound familiar? You’ve likely heard this classic introduction to fairy tales, some of which originated thousands of years ago. If there is anything certain about homo sapiens, it’s that we love stories. Every culture on the planet has created and shared narratives to help them make sense of their lives and the cosmos.

Comparative Literature, often called “Comp Lit,” is an academic discipline that analyzes various texts and discourses in order to develop theories and draw conclusions about the world. A scholar of Comparative Literature might compare ancient and modern texts, or texts in two or more languages, among many other possibilities. There are Comparative Literature scholars, for example, of fairy tales and folklore, environmental literature, postcolonial literature, memory and trauma, translation, and on and on.

In fact, one of the most exciting aspects of Comparative Literature is its broad and dynamic possibilities. This is one major reason why intellectually curious students from all over the world continue to study Comparative Literature. That said, what “Comparative Literature” signifies exactly will very much depend on factors such as geographical region, academic setting, time period, and more. Ultimately, context is vital, which is fitting indeed as Comp Lit scholars must grapple with multiple contexts in their analyses.

So, to help you better grasp the discipline known as Comparative Literature, and why people study it, this article will take you through its origins and history, as well as many other aspects, such as how it differs from English and “World Literature,” and some of the top schools that offer Comparative Literature degrees.

To understand Comparative Literature, it helps to first understand what “literature” itself is. This is by no means a simple task, as definitions vary widely and the “literature” of Comparative Literature has become increasingly broad in recent generations.

Following the Encyclopaedia Britannica, “literature” refers to a body of written works, typically imaginative works (i.e. fiction) of poetry or prose that possess a certain excellence in content and form. Now, the study of literature has also long been associated with the study of the literature of a particular culture and/or language: e.g. British literature or English literature, African literature, French literature, Arabic literature, and so on.

The history of translation is very much part of the comparative literature origin story, as translations only occur when cultures and languages meet and need to be mutually understood. Traditionally, scholars of Comparative Literature work and study in at least two languages, if not three or more. One such example is one of the twentieth century’s greatest literary scholars, Erich Auerbach (1892-1957), who was German and Jewish and thus lived in exile in Istanbul. There, without the help of his library, and well before the Internet, of course, he composed his masterwork Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature. This monumental study analyzed ancient and modern texts in several languages (including Latin, French, English, Italian, Spanish, and German), including a famous examination in “Oddyseus’ Scar” that compares Homer’s Odyssey and the Biblical Book of Genesis (more specifically, Odysseus’ return and the binding of Isaac, respectively).

While Auerbach’s style of comparative literary studies is impressive and a landmark in Comparative Literature, the academic discipline has developed dramatically since the publication of Mimesis in 1945. Comparative Literature has in many ways come to signify a more fluid and dynamic field. To follow this thread, it helps to compare Comp Lit with other related disciplines, such as English literature and “World Literature.”

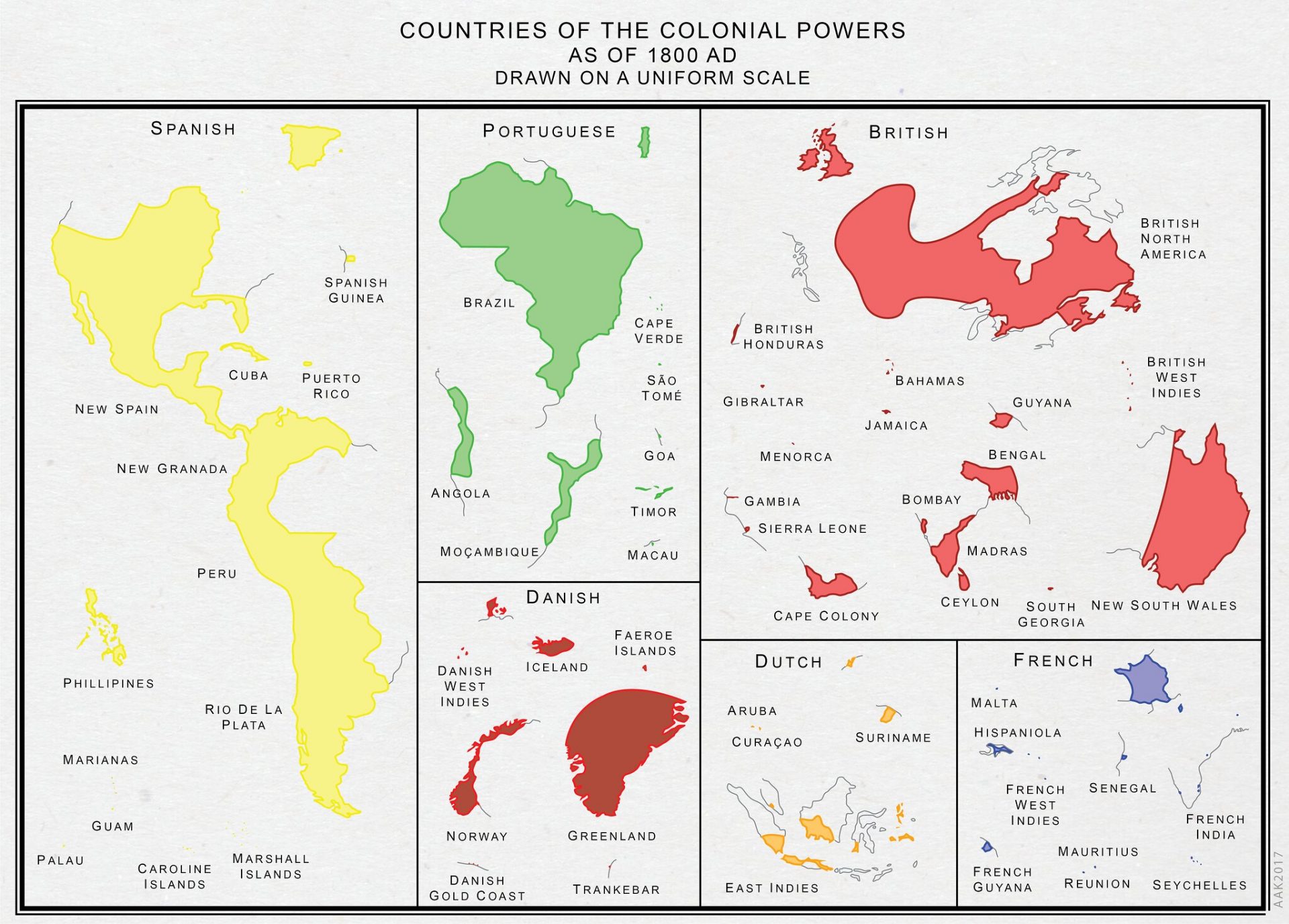

Comparative Literature developed particularly strongly for three main reasons: the development of academic institutions around the world from the Enlightenment onward, the codification of “Literature” as a field of study within these institutions, and a globalizing world. This process of globalization, itself fueled primarily by forces of empire and capital, led to a theory of “World Literature” that can be traced in large part to the German polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832).

You see, Goethe was a writer himself and highly immersed in the culture and society of his time. In “Conversations with Eckermann on Weltliteratur [World Literature],” he compared a Chinese novel with the French folk poet Charles Béranger. While his countryman Johann Gottfried Herder had theorized the importance of a national language and literature for the unity of a given people (expressed in their Volkgeist, or national spirit), Goethe argued that “National literature is now an unmeaning term; the epoch of world literature [Weltliteratur] is at hand, and everyone must strive to hasten its approach”.

World literature, under Goethe’s term, is thus a precursor for Comparative Literature, and many Comp Lit scholars do in fact continue to theorize the term “World Literature” and study literature that crisscrosses the globe (such as the participants of Harvard’s Institute for World Literature, or IWL.) For example, a Comparative Literature scholar of environmental literature, who might be termed an “ecocritic,” could consider comparing Caribbean literature with Polynesian literature by analyzing the way that writers of both regions explore the impact of rising seas and other effects of climate change.

So, world literature tends to have a more global thrust whereas English literature, or any national literature, tends to be more insular. Traditionally speaking, a student of British literature, French Literature, or Japanese literature, would stick to studying the literature and other cultural expressions of the British Isles, mainland France, and Japan. More recently, however, the study of such literatures has expanded to reckon with the histories of colonialism and imperialism, which took English and French, for example, all over the globe.

To circle back to the example of a Caribbean literary scholar above, this person may well study literature in English, French, and Spanish, not to mention various forms of Creole (such as Haitian Kreyòl). A scholar of Spanish might study both the literature of Spain as well as the Hispanophone literature of Latin America. While the study of one national literature continues to prove popular, it has become more common for scholars to study multiple literatures, such as postcolonial literatures, where writers often produce literature in the language of the former colonizer. Take, for example, the Martinican poet and politician Aimé Césaire, who wrote in masterful French while also overseeing Martinique’s transition from a colony to a département d’outre-mer, or overseas territory.

We can note here, however, the distinction implicitly drawn by the French administrative term département d’outre-mer. By saying “overseas,” they establish European France as the center, with Martinique and Guadeloupe as peripheral territories. Comparative Literature scholars, such as Pascale Casanova and Lawrence Venuti, have often shown interest in studying the relationship between literary centers and peripheries. For example, one might study the literature of both “L’Hexagone” (the France of Europe) as well as francophone Caribbean literature in order to better understand the nature of identity for modern French citizens who live or lived in the French Caribbean, as well as the relation between Caribbean writers and the French literary canon.

Similarly, students of “English,” particularly graduate students, increasingly study anglophone literature from around the globe, rather than purely British or American literature, though that continues to maintain its popularity due to the richness of its authors (Shakespeare, Dickens, Melville, Woolf, Orwell, Toni Morrison, Cormac McCarthy, etc.). Both English and Comparative Literature departments and programs now regularly offer classes with literature in translation, e.g. “World Literature,” “Postcolonial Literature,” etc. This enables a greater number of students to take the courses than if the texts were in their original language(s).

As you can begin to see, the distinctions between Comparative Literature, World Literature, and English Literature are not always simple and clear-cut. In general, though, World and Comparative Literature tend to encompass, though not always, multi-lingual, transhistorical, and cross-cultural analysis. English, French, or Spanish literature, on the other hand, may have a more restricted corpus based on the works available in those languages.

By focusing on the major aspects common to Comparative Literature theory and practice around the world today, we can start to narrow down the definition of Comparative Literature as it currently stands as an academic discipline.

As should be clear from the preceding sections, Comparative Literature is a relatively modern term that has a long and complex history. Nonetheless, it has become relatively standardized as an academic discipline.

So, here are a few key aspects of Comparative Literature to help develop a more detailed definition of how it operates in top academic universities around the world today.

Students become Comparative Literature scholars for many reasons. Many students pursue Comp Lit because they would like to become educators, while others may come to Comp Lit by studying a language or through a General Education requirement. (I myself wanted to read Albert Camus in the original French after being introduced to his works in high school.)

Generally speaking, Comparative Literature courses excel at nourishing students’ imaginations and honing their critical thinking and writing skills. In this way, many students can benefit from taking Comparative Literature courses.

Here are some common professions for literature students:

Of course, the critical writing and thinking skills developed over the course of a Comparative Literature degree prove beneficial in nearly any occupation, not to mention in day-to-day life. This is no doubt why great actors and directors such as Emma Watson and Martin Scorsese have studied literature. To study literature is, in so many ways, to study life itself in all its ambiguities and complexities.

Here’s a list of roughly twenty of the world’s foremost universities for literary studies. The universities are located in the United States, unless specified.

This is, of course, only a partial list, and students may pursue what is very similar to a Comparative Literature program even though they study English or another language.

Many of these schools are considered extremely prestigious, and Comp Lit scholars themselves may study “prestige” in the context of the World Republic of Letters (Pascale Casanova’s term). Think, for example, of the prestige carried by a Nobel Prize in Literature, or of the effects it may have on our conception of “literature,” such as when the singer-songwriter Bob Dylan won it in 2016 for “having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.”

Ultimately, however, you don’t need a prestigious university program to study Comparative Literature. You can always study literature on your own and from the comfort of wherever you may be. All you really need are books and stories to read and the time to allow your mind to draw parallels despite (or due to) differences in country, language, historical period, etc.

Comparative Literature is an exciting and dynamic field that reflects a general shift in comparative studies away from a focus on Western European traditions and toward a more global consciousness. It encourages multilingual, transhistorical, and cross-cultural frameworks that allow for new connections to be made and older ones to be reconsidered.

Comparative Literature scholars may tackle everything from Kafka and K-Pop to Camus and the climate crisis (and everything in between). These exciting possibilities continue to attract students from around the world as they gain greater empathy and boost their critical thinking and writing skills in the pursuit of a Comparative Literature degree.